An exhibition of archival photographs restores women to the historical narrative of ‘New Nepal’, and on their own terms.

By Riddhi Dastidar,

When you walk into the Feminist Memory Project you’re struck by how all the women photographed seem to have been caught in the middle of doing something – even if that was just choosing to be photographed. They’re not selling anything, neither product nor trauma, nor their own sex appeal. They often look straight at you.

The writing on the wall says: ‘To become public is to be seen and accounted for in history’.

The Feminist Memory Project (FMP) reconstructs the history of Nepal to include women in a narrative from which they’ve been largely omitted. Nepal transitioned to a democratic republic as recently as 2006. The transition was violent; it followed a people’s movement against the Rana monarchy that claimed over ten thousand civilian lives in ten years alone.

Many of the insurgents were women – living underground with the Maoist movement, away from their families. There have been sporadic instances of awards over the years, but no coherent narrative about the women’s role in creating a ‘New Nepal’. The FMP rectifies this by documenting history through the memories of Nepali women.

Their entry-point is letters and photographs – documents that can be preserved, and carry emotional value. One could call these a sort of evidence. Our time of constant coverage makes it inescapable how little women’s evidence can count for – the Brett Kavanaughs and M.J. Akbars of the world are protected by ‘himpathy’ and impunity while the Dr Fords and Priya Ramanis fight death-threats and court cases. When it comes to minority groups it’s even bleaker.

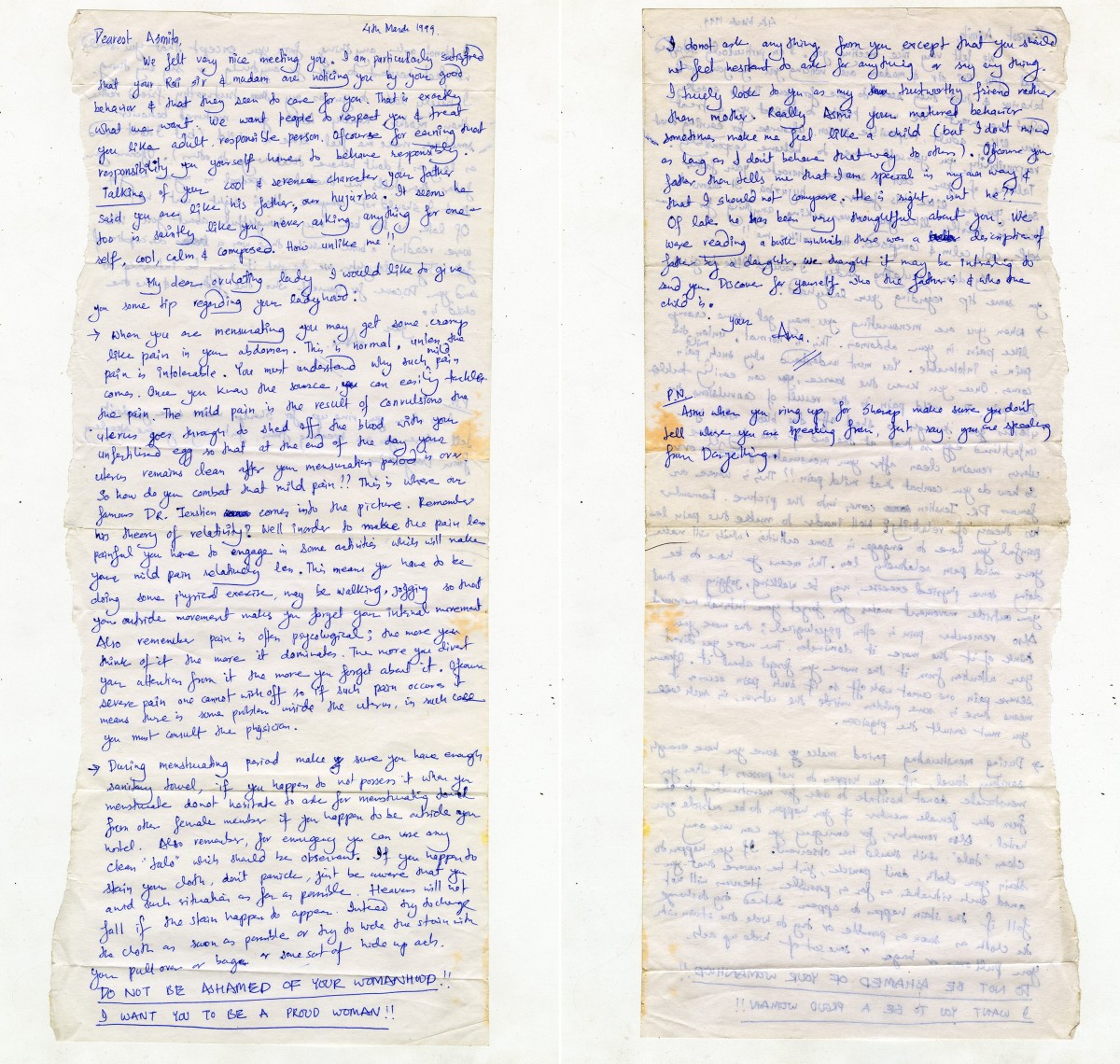

In response, we see the rise of alt-histories with Black History Month, Dalit History Month, and now the Feminist Memory Project. I ask NayanTara, one of the two curators of the project, to tell me something that surprised her about the process. She points me to a letter written by Hisila Yami – a founding member of the Maoist Party, from her time underground. It’s full of practical advice to her daughter on how to deal with period-cramps, acknowledging that sometimes nothing helps – and exhorting her not to hesitate in asking for what she wants.

Today, Yami has a reputation as a ruthless politician at the helm of a ruling coalition-party, with a number of corruption charges against her. “To see how she raised her daughter in absentia, even how forthcoming she was about contributing to the archive was unexpected,” NayanTara says. This kind of eagerness was not unique to Yami. Women and their families were usually hungry to participate, and stunned that someone was interested in their lives.

There was an overarching sense of urgency to document these material memories – many of the subjects had died – and an understanding that this could change the way women’s history would be talked about in years to come.

The FMP is an initiative of photo.circle, a Nepali photography collective founded by NayanTara in 2007. The process of putting together the archive was intense and fast. Women’s collectives and NGOs helped connect the team to networks of women. The team ensured that they were armed with a depth of knowledge and feminist understanding before setting foot in the field. They held reading groups and public screenings, to discuss questions like what it means to have a women’s space, and what we speak of when we say ‘history’.

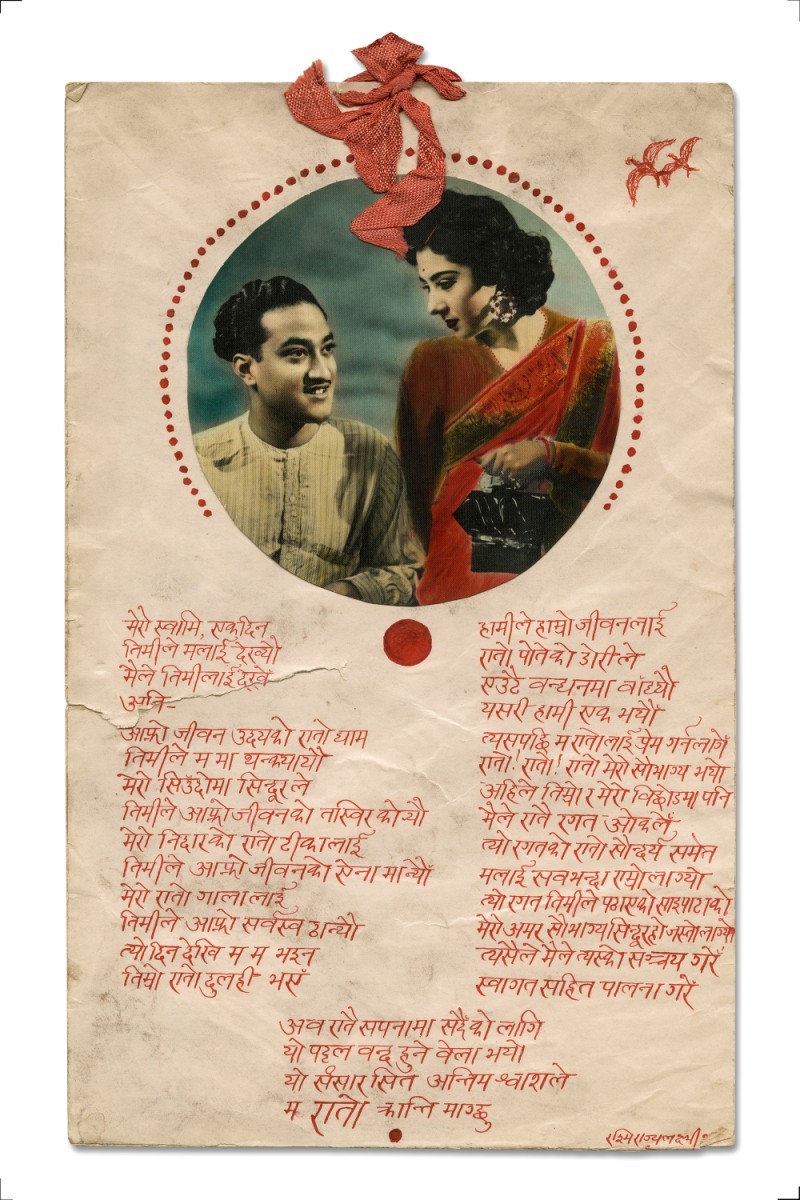

The project doesn’t canonise or try to construct a singular heroic narrative. Like Yami, there are women across the political spectrum, including those who were pro-monarchy. There are dramatic images of aristocrat Rashmi Rajya Laxmi Shah, posing in trousers with her playwright husband. A supporter of the Nepali Congress against the monarchy, she ultimately committed suicide in exile after her husband was killed at a revolt, leaving behind a love-poem to him, now part of the archive.

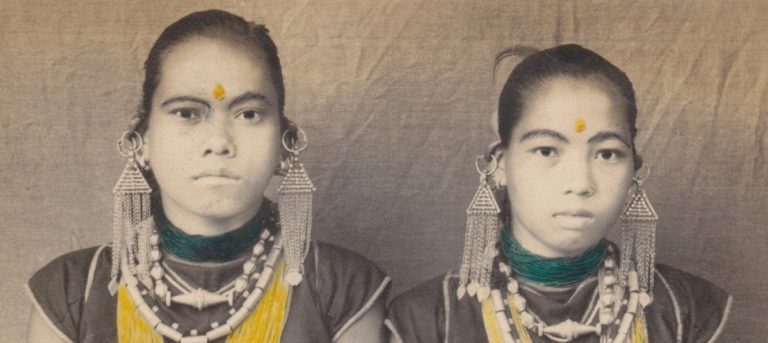

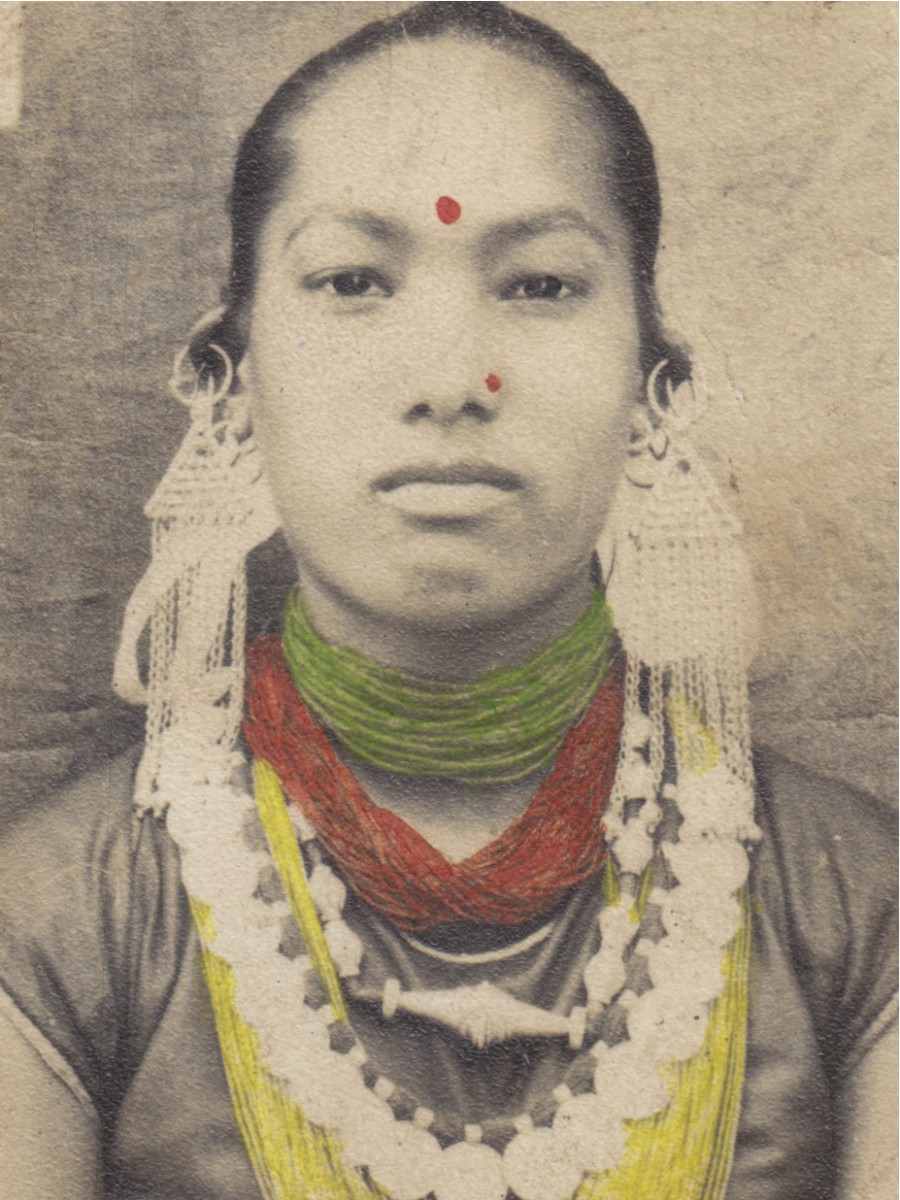

The image that stays with me for days is a series of studio-portraits from the Karjahi movement. In one of the first instances of mass revolt, women bonded-labourers beat up their landlord and then resisted arrest by the police. Afterwards, they went to a studio to be photographed. I’m inescapably reminded of today’s selfie-culture of documentation. Across years and geographies, there it is – the desire to resist, to control the narrative – the female gaze.

Women from all walks of life gather for a mass meeting in Kathmandu to submit a letter of protest to the government following the rape and murder of sisters Namita and Sunita Bhandari in Pokhara that rocked the country.

In the future, NayanTara hopes for many things – to provide the younger generation a fuller picture of Nepal – as she has begun to do with an arts and education programme in schools. To encourage more intergenerational transactions with younger Nepali feminists. To bring the FMP to more exhibitions in more countries, to collaborate with more academic institutions and to invite other practitioners to embark on their own research journeys.

Since late July 2018, Nepal has been in new foment with countrywide protests over the unsolved rape and murder of schoolgirl, Nirmala Pant – a parallel to the unsolved Namita-Sunita murders in 1980. The case drew one of the first mass rallies of women out on the streets (now archived in an FMP picture). In a #MeToo world where we do not escape news of women being brutalised everyday, there is something you come away with after visiting the Feminist Memory Project.

It’s not escapism. It’s something grittier, more fundamental. One is struck above all by a sense of hope – a reminder that change is generational – and even if we don’t live to see it, it’s important that we hold it fast and sing it home.

The Feminist Memory Project was exhibited as part of the Khoj International Artists Association’s Curatorial Program at Studio Khirki in New Delhi.

This article was originally published at The Wire and is republished on Nepalisite.com with permission.

Riddhi Dastidar is a writer of poetry and non-fiction, and a Gender Studies scholar at Ambedkar University Delhi.