Will an ambitious Chinese-built rail line through the Himalayas lead to a debt trap for Nepal?

Jagannath Adhikari, Curtin University

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has ambitions to reshape the global economy by connecting more than 60 countries across Asia, Europe and Africa through trade and infrastructure projects. All told, it’s envisioned that nearly two-thirds of the world’s population will in some way be connected through BRI projects in the future. Some economists estimate BRI could increase global trade by 12%.

Despite these benefits, many questions have been raised about China’s motivations for the initiative, and whether Beijing can afford the US$1 trillion it has committed to infrastructure projects and its partners can afford the debt they are taking on. Some fear BRI could be a Trojan horse for global domination through debt traps.

Sri Lanka is often cited as a cautionary tale. Unable to repay the loans on a US$1.5 billion port construction project, the Sri Lankan government agreed to give China a 99-year lease on the port instead. The ports and shipping minister said at the time:

We had to take a decision to get out of this debt trap.

Nepal takes the plunge

Despite fears over loans they can’t pay back, many small countries have accepted BRI as an alternative pathway to economic prosperity. Nepal is one of them – it entered into BRI last year with great enthusiasm.

Then in June of this year, Nepali Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli travelled to China to sign agreements worth US$2.4 billion on everything from infrastructure and energy projects to post-disaster reconstruction efforts.

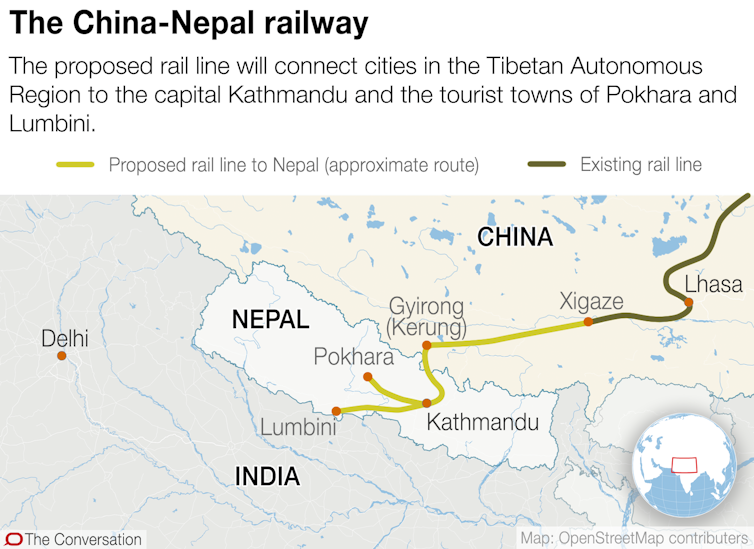

The highlight of the deals is an audacious plan to build a railway line through the Himalayas. The line will link the Tibetan border town of Kerung with the Nepali capital, Kathmandu, and tourist towns of Pokhara and Lumbini (Buddha’s birthplace). The railway is being trumpeted as a potential windfall for Nepal’s tourism industry, with some 2.5 million Chinese tourists expected to visit annually.

If the rail line is developed as proposed, Nepal would also be well placed as a major transit hub for trade between China and its rival, India. One study estimates Nepal’s trade could be boosted by 35% to 45% when the rail line and other BRI infrastructure projects are completed.

The Chinese government has already conducted a pre-feasibility study on the Kerung-Kathmandu railway. It estimated the 72.25km line from the Chinese border to Kathmandu would cost US$2.25 billion. (Other estimates say the cost might be much more.) Nepali railway officials say an incredible 98.5% of the line would run through tunnels and across bridges due to the forbidding, mountainous terrain.

Is Nepal falling into a debt trap?

The main debate in Kathmandu now is whether this proposed rail line is technically and financially feasible, and if it is someday completed, whether it’s destined to become a white elephant – an expensive but vastly underutilised transportation line.

Then there is the question of cost. Besides Sri Lanka’s struggles to pay back the US$8 billion in total it now owes Chinese firms, many other countries are in similar straits.

Economists worry that Laos, which has seen its debt reach 68% of GDP, will have difficulty paying off its share of a US$6 billion rail line being built by China. And in the Maldives, the opposition claims the country is facing a looming debt trap, with US$92 million in annual payments due to China to pay off an airport upgrade and bridge project – roughly 10% of the entire budget.

In Nepal, the burning question has been whether the trans-Himalayan rail line and other infrastructure projects would be built with similar loans, or if the government would be able to secure grants from China instead.

Economists and planners in Nepal believe the rail line would be beneficial to the country’s development, particularly because it would end Nepal’s reliance on its traditional ally, India, for trade, fuel, food and medical supplies.

A two-month blockade of the main trade route between Nepal and India in 2015 gave Nepali politicians greater rationale for diversifying the country’s trade partners and becoming better connected to global trade routes. The greater connectivity with China is also expected to boost Nepali exports of special herbs and agricultural products that are in high demand in China.

But given the debt problems in Sri Lanka and other countries, the previous Nepali government was initially hesitant to follow the same path in its dealings with China. Last year, it pulled the plug on a US$2.5 billion hydropower plant being built by a Chinese firm because of the lack of a competitive bidding process.

But since Oli returned to power in February, he has pursued much more Beijing-friendly policies. Last month, he reinstated the hydroelectric plant contract. And though Nepal is still seeking grants from China to build the trans-Himalayan railway, it’s unclear whether Oli will make this a precondition to starting construction.

China is offering soft loans to fund the railway instead. It also sweetened the deal in September by giving Nepal access to four of its seaports, which will give Kathmandu a viable trade alternative to Indian ports for the first time.

Thus far, Nepal and China have not come to an agreement on the funding question over the BRI projects and construction has yet to start.

Thinking beyond debt traps

Indian politicians and media outlets have been sceptical of China’s efforts to woo Nepal, raising fears that BRI is a masquerade for Chinese domination through debt-swap arrangements. But India’s real concern is losing its long-standing influence over Nepal, with which it enjoys a US$5 billion trade surplus.

For Nepal and other small countries in the region, however, the benefits that BRI can bring – namely improved infrastructure and greater connectivity to the world – do appear to be too good to pass up. After all, Nepal’s main concern is economic growth, development and improved livelihoods for its people.

For the country to truly benefit from these projects, it needs to enter into them cautiously, with the right funding plans in place. The government views these projects as potentially massive political victories and could overlook concerns over safety issues and financing when signing deals with China.

But Nepal must not fall into the same debt trap as Sri Lanka; otherwise, its aspirations of a brighter future could turn into a mirage.![]()

Jagannath Adhikari, Adjunct Research Fellow, School of Design and the Built Environment, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.